Norm of whiteness

In Norway, a "whiteness norm" is expressed in various ways. One seemingly innocent example is bandages and colored pencils labeled as "skin-colored." The question is, “skin-colored” for whom? Who are the bandages made for, and who is being forgotten? Whiteness is often seen as universal and inconspicuous, and automatically, not being white becomes more noticeable.

What is it like to stroll down Karl Johan street as a white person? The question might sound strange. But if we reverse it and ask what it’s like to stroll down Karl Johan as a person of color, many would have experiences and stories about looks and questions.

Being perceived as different can in itself be uncomfortable. Being labeled as different also makes one more vulnerable to prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination.

In the cultural sector, it’s important to consider how ideas about quality, good taste, style, high and low culture may be influenced by whiteness norms. What we now consider high culture has roots in a time when Europeans colonized other parts of the world.

- Which art and cultural expressions have status today?

- How does our history influence our understanding of quality and relevance?

- Who decides or influences which expressions gain status?

In the video Already Here, directed by Camara Lundestad Joof for Arts and Culture Norway, artists of color share their experiences in the field.

Audio description: The video shows the artists Ahmed Umar, Amy Black Ndiaye, Camara Lundestad Joof, Fadlabi, Iselin Shumba, Noah Løchting Williams, Rita Paramalingam, Sandra Mujinga, Thomas Talawa Prestø, and Wolman Michelle Luciano. They share their stories, edited together in a mixed up fashion.

Racism

=

systemic prejudices

The term "whiteness norm" overlaps with the term "racism." Racism involves prejudice and the devaluation of people based on ideas about ethnicity and skin color. It’s essential to note that racism isn’t just about prejudices but prejudices put into a system. The whiteness norm highlights how being white provides security.

- Applicants with Pakistani names have a 25% lower chance of being invited to a job interview compared to equally qualified applicants with Norwegian names.

- 6% of people with immigrant backgrounds have experienced hate crime, compared to 1% in the general population.

- People with multicultural backgrounds made up only 3% of sources in Norwegian media in 2020. If immigrants are portrayed from a problem perspective, their country of origin is twice as likely to be mentioned compared to articles with a resource perspective.

- In Norway’s 100 largest public organizations, none of the top leaders had multicultural, non-Western backgrounds in 2023, with only 1.02% in leadership teams.

Racism is more than overt prejudice and hatred

Racism is often associated with severe cases of hate crimes, hate speech, or similar events. It’s crucial to understand that racism also occurs in less obvious forms. Understanding racism as systemic helps us see how prejudices, norms, and assumptions affect the entire society, including ourselves.

Racism doesn’t need to be intentional

It’s often less helpful to talk about being racist or not and more useful to consider how different actions and omissions can have racist consequences.

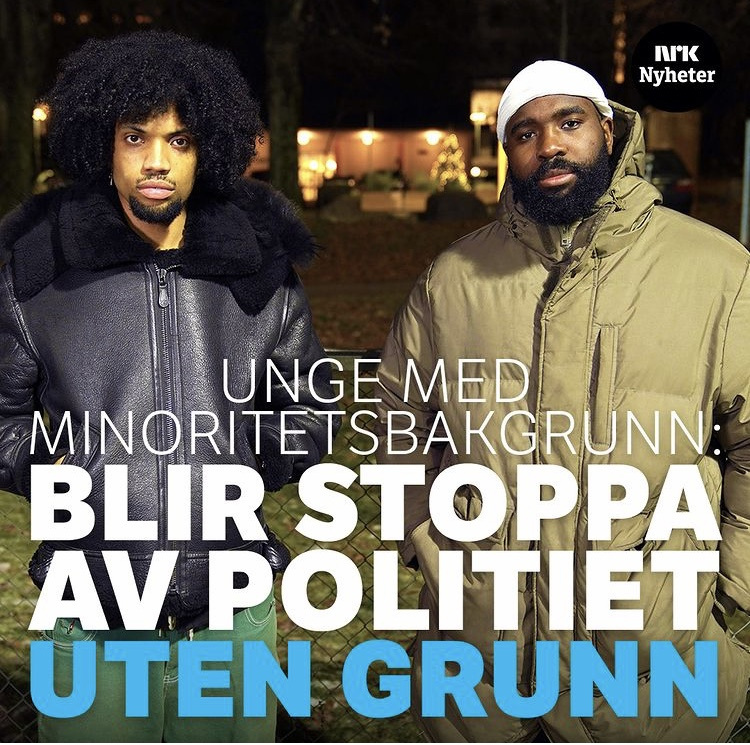

The picture says: Young people with minority background: Stopped by the police for no reason.

The picture says: Tariq (27) feels he has to “prove” he is nice.

Suspicion and prejudice are stressful to live with. To NRK, Tariq Ashad says that he experiences prejudice against ethnic minority men from society at large, and that he feels he must prove that he is kind. His experience is supported by a research report.

Racialization

The whiteness norm largely involves power and societal ideas about "whiteness" rather than skin color. Who is considered white is not necessarily a given.

The term racialization describes the processes through which people are assigned an ethnicity. For example, Italians and Irish were previously defined as non-white in the United States. This shows that ethnicity isn’t based solely on appearance but that politics, history, and power relations affect how people are racialized.

Colour blind?

"I don’t see color" is a well-intentioned response in discussions about equality and diversity. “Why should we focus so much on differences; we’re all human?”

The goal of equality work is for everyone to be met as unique individuals and to participate on equal terms, regardless of who they are.

But equality doesn’t happen on its own. When some groups still encounter barriers and discrimination in the cultural sector, we need to talk about this.

It’s also easy to claim to be "colorblind" if you’ve never experienced discrimination based on skin color.

Not caring about differences is a misguided equality strategy that, at worst, promotes sameness rather than equality. Valuing diversity means highlighting and appreciating our different experiences and perspectives, which enrich our community.

Summary:

4 key anti-racist perspectives

- Racism is not just overt prejudice or hatred but a structural issue expressed through norms.

- Racism doesn’t have to be intentional. Unconscious biases among people and within systems can produce racist outcomes.

- Our understanding of "ethnicity" and "race" is socially constructed, and while these categories aren’t real, the social construction of "race" has real effects.

- Being "colorblind" isn’t productive – we must talk about differences to counter racist discrimination.

Sámi and national minorities

Norway has always been a multicultural society. Norwegians and Sami people have a long historical presence in the country, while Kvens and Forest Finns are examples of minorities with several centuries of connection to Norway.

Because the norm of whiteness privileges white culture, it also acts oppressively against the Sami and other national minorities – Kvens/Norwegian Finns, Norwegian Roma, Romani people, Forest Finns, and Jews. The norm of whiteness creates a narrow understanding of who constitutes Norwegian society and who truly belongs here.

The lack of knowledge about Sami and national minorities' culture, history, and political interests creates prejudice and exoticism. This lack of knowledge also means that much of the population misses out on the richness these minority cultures bring with them.

- 11% of people with Sami heritage have experienced discrimination in the workplace.

- 3 out of 4 young Sami have faced discrimination.

- 41% report experiencing harassment multiple times a year.

- A full 95% state that they encounter prejudice against Sami culture within mainstream society.

- 1 in 3 Norwegians has a negative impression of Norwegian Romani and Romani people.

- 9 out of 10 Norwegians report having learned nothing or very little about Kvens/Norwegian Finns, Forest Finns, Norwegian Roma and Romani people in school.

To promote the Sami language, after over 100 years of oppression, Sami place names are now being highlighted on signs. However, anti-Sami attitudes still exist among the population, and many Sami signs are frequently vandalized.

The norm of whiteness and religion

The norm of whiteness also means that Norwegian and European cultural history is seen as the standard, while other cultures and religions are regarded as different and often encounter prejudice.

A 2018 attitude survey showed that a total of 32% of Norwegians reported having a somewhat or very negative attitude toward Muslims. For Jews, 9% held a negative attitude, with 7% and 6% expressing negativity toward Hindus and Buddhists, respectively. Five percent held negative views toward Christians.

Religion can significantly impact one’s chances of getting a job. If an application indicates that the applicant is associated with a religious youth organization, the chance of being called for an interview can be reduced by about a third. This effect is noticeable for applicants with both Christian and Muslim affiliations.

Muslim applicants often face a double disadvantage—both due to their name and their religious background. This results in considerably lower chances of being considered for interviews compared to applicants without religious affiliations.

Muslim women who wear the hijab frequently experience a combination of sexism and Islamophobia, with the added strain of their headscarf being a frequent topic of public debate.

"Believe it or not, I don’t wear hijab for anyone."

“When men who look like me or have a similar religious background tell me they like that I wear the hijab, I say: I don’t wear it for you. I don’t wear it for your gaze. I would say the same to those who are provoked by my hijab. Believe it or not, I don’t wear the hijab for anyone. I don’t wear it to satisfy those who romanticize it or to provoke those who despise it.”

This is written by poet, author, and editor at Fett, Sumaya Jirde Ali, in VG.

Are you uncertain about terminology when discussing ethnic diversity? Here you can read about the terms that we in Balansekunst use to describe different groups (in Norwegian).